Other than material trading, what did trans-Saharan caravans bring to Ghana?

Salt from the Sahara desert was one of the major trade appurtenances of ancient West Africa where very footling naturally occurring deposits of the mineral could be found. Transported via camel caravans and by gunkhole forth such rivers equally the Niger and Senegal, salt found its mode to trading centres similar Koumbi Saleh, Niani, and Timbuktu, where it was either passed further south or exchanged for other goods such equally ivory, hides, copper, atomic number 26, and cereals. The virtually mutual substitution was salt for golden dust that came from the mines of southern West Africa. Indeed, salt was such a precious commodity that information technology was quite literally worth its weight in gold in some parts of W Africa.

Table salt Slabs, Timbuktu

The Salt Mines of the Sahara

The necessity for salt in aboriginal West Africa is here summarised in an extract from the UNESCO Full general History of Africa:

Salt is a mineral that was in great demand particularly with the beginning of an agronomical mode of life. Hunters and food-gatherers probably obtained a large amount of their salt intake from the animals they hunted and from fresh plant food. Salt but becomes an essential condiment where fresh foods are unobtainable in vey dry areas, where trunk perspiration is also commonly excessive. Information technology becomes extremely desirable, however, amongst societies with relatively restricted diets, as was the case with abundant agriculturalists. (Vol 2, 384-five)

In addition, table salt was always in peachy need in order to better preserve dried meat and to give added taste to food. The savannah region southward of the western Sahara desert (known as the Sudan region) and the forests of southern West Africa were poor in salt. Those areas near the Atlantic coast could obtain the mineral from evaporation pans or humid sea water, just bounding main salt did not travel or go on well. A third alternative was salt derived from the ashes of burnt plants like millet and palms, but again these were not so rich in sodium chloride. Consequently, for most of the Sudan region, salt had to come from the north. The inhospitable Sahara desert was the chief natural source of rock salt, either acquired from surface deposits acquired by the desiccation process such equally found in erstwhile lake beds or extracted from relatively shallow mines where the common salt is naturally formed into slabs. This common salt, which was a flossy-greyness color, was far superior to the other sources of common salt from the sea or sure plants.

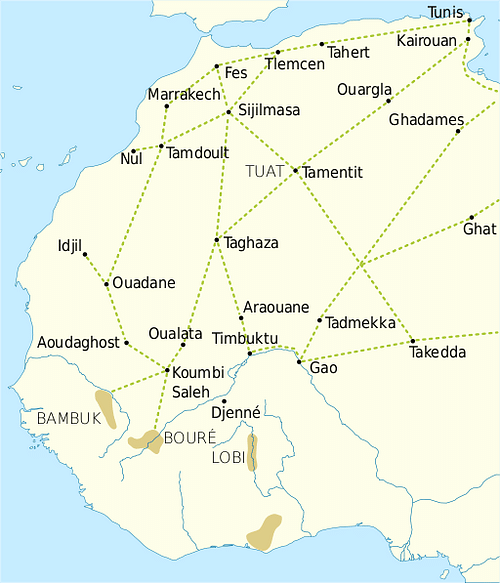

Trans-Saharan Trade Routes

When exactly common salt became a trade commodity is unknown, only the substitution of common salt for cereals dates back to prehistory when desert and savannah peoples each looked to proceeds what they could not produce themselves. On a larger scale, camel caravans were likely crossing the Sahara from at least the starting time centuries of the 1st millennium CE. These caravans would be run by the Berbers who acted as center-men between the Due north African states and West Africa. Salt was their major merchandise expert but they also brought luxury items like glassware, fine cloth, and manufactured appurtenances. In addition, with these trade goods came the Islamic religion, ideas in art and architecture, and cultural practices.

Whoever controlled the salt merchandise also controlled the gold trade, & both were the master economical pillars of various West African empires.

Table salt, both its product and merchandise, would dominate W African economies throughout the 2nd millennium CE, with sources and trade centres constantly changing hands as empires rose and savage. The salt mines of Idjil in the Sahara were a famous source of the precious commodity for the Republic of ghana Empire (half-dozen-13th century CE) and were still going stiff in the 15th century CE. In the 10th century CE the Sanhaja Berbers, who controlled the table salt mines at Awlil and Taghaza and transportation through merchandise cities like Audaghost, began to challenge the Ghana Empire's monopoly of the trade. In the 11th century CE the Awlil mines were in the hands of Takrur, but it would be the Republic of mali Empire (1240-1645 CE), with its capital at Niani, that dominated the sub-Saharan salt trade following the collapse of the Ghana Empire. However, semi-contained river 'ports' like Timbuktu began to steal trade opportunities from the Mali kings farther west. The next kingdom to dominate the region and the movement of table salt was the Songhai Empire (xv-16th century CE) with its great trading capital at Gao.

Salt may have been a rarity in the savannah simply at desert mining towns like Taghaza (the primary Sudan source of salt up to the 16th century CE) and Taoudenni, the article was still so abundant slabs of rock salt were used to build homes. Naturally, such a valuable money-spinner as a salt mine attracted competition for ownership, as when the Moroccan leader Muhammad al-Mahdi attempted to muscle in on the market by arranging for several prominent Tuareg salt traders to be murdered at Taghaza in the mid-16th century CE. Quite literally, whoever controlled the common salt merchandise likewise controlled the gold trade, and both were the principal economic pillars of the various empires of West Africa's history.

Trans-Saharan Camel Caravan

The 14th-century CE Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta, who visited W Africa c. 1352 CE, gives a lengthy clarification of life in the common salt mine settlement of Taoudenni:

It is a village with no attractions. A strange thing about information technology is that its houses and mosques are built of blocks of common salt and roofed with camel skins. There are no trees, but sand in which there is a salt mine. They dig the ground and thick slabs are found in it, lying on each other as if they had been cut and stacked under the ground. A camel carries 2 slabs. The but people living at that place are the slaves of the Massufa, who dig for the common salt.

(quoted in de Villiers, 121-122)

Transportation

The common salt slabs, relatively durable just unwieldy, were loaded onto camels, each animal carrying two blocks that weighed up to 90 kilos (200 lbs) each. A camel caravan could be equanimous of anywhere from 500 to several thousands of camels in their heyday. The first caravans probable crossed the western Sahara in the 3rd century CE, if not earlier, but the practice really took off from the 9th to 12th century CE. When the caravans arrived at a trading eye or major settlement in the Sudan region, the salt was exchanged for goods to carry dorsum across the desert on the return journeying; typically such loads included gold, leather, creature skins, and ivory. The salt could be used in the communities effectually the trading centres or merely transported on by boat forth such rivers equally the Niger, the Senegal, and their tributaries. Finally, the salt was cutting upwards into smaller pieces and porters carried it on their heads to its final destination - the villages of W Africa's interior.

Worth its Weight in Gold

Salt was a highly valued commodity not just because it was unobtainable in the sub-Saharan region but because information technology was constantly consumed and supply never quite met the total need. There was also the problem that such a bulky detail cost more to send in pregnant quantities, which but added to its high price. Consequently, table salt was very often exchanged for gilt dust, sometimes even pound for pound in remote areas, with merchants specialising in ane of the bolt. Indeed, such was the stability of the mineral'south value, in some rural areas small pieces of salt were used as a currency in trade transactions and the kings of Ghana kept stockpiles of salt alongside the gold nuggets that filled their impressive royal treasury. The passage of such a valuable item from one trader to another provided ample opportunity to increase its value the further it went from its source in the Sahara.

An anonymous Arab traveller of the 10th century CE recorded the delicate operation of bulk trading between table salt and golden merchants, sometimes chosen 'the silent trade' where neither party really met confront to face up:

Bang-up people of the Sudan lived in Ghana. They had traced a boundary which no one who sets out to them ever crosses. When the merchants attain this boundary, they identify their wares and cloth on the basis and and then depart, and so the people of the Sudan come begetting gold which they exit abreast the trade and so depart. The owners of the merchandise then return, and if they were satisfied with what they had establish, they take it. If non, they go abroad again, and the people of the Sudan return and add to the price until the bargain is concluded.

(quoted in Spielvogel, 229)

Transporting Salt on the Niger River

Even the passage through of salt could be a lucrative source of income for rulers. For example, the Arab traveller Al-Bakri, visiting the Sudan region in 1076 CE, describes the duties on salt in the Ghana Empire which were, unlike with other goods similar copper, taxed twice: "On every donkey-load of salt the King of Republic of ghana levys one aureate dinar when it is brought into his country and 2 dinars when it is sent out" (quoted in Fage, 670). In another example, Timbuktu operated as the middle-trader in this exchange of northern and Westward African resources. A 90-kilo cake of salt, transported by river from Timbuktu to Djenne (aka Jenne) in the due south could double its value and be worth around 450 grams of aureate. Every bit the Tarikh al-Sudan chronicle, compiled c. 1656 CE, notes:

Jenne is one of the greatest Muslim markets, where traders carrying salt from the mines of Taghaza meet traders with the gilt of Bitou…It is considering of this blessed town that caravans come to Timbuktu from all points of the horizon.

(quoted in Oliver, 374)

Even today, the common salt trade continues, although the deposits are running out and the salt merchants tin no longer command gilded dust in exchange. Saharan salt from Taoudenni is still transported past Tuareg camel caravans, the still-90-kilo slabs now ultimately destined for the refineries of Bamako in Mali.

This article has been reviewed for accurateness, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1342/the-salt-trade-of-ancient-west-africa/

0 Response to "Other than material trading, what did trans-Saharan caravans bring to Ghana?"

Post a Comment